I first noticed a small, firm lump on the right side of my neck, above my clavicle, when I was 26. I panicked because a web search showed that that is the location of a lymph node whose swelling is often the first sign of cancer metastasis from the chest. The doctor ordered an emergency ultrasound. The ultrasound was inconclusive, so he ordered a neck CT scan. I worried for a week while I waited for the CT. The doctor finally told me that the lump was only a muscle knot, and that I could get an MRI if I was concerned about the muscle. I felt completely relieved and was afraid of claustrophobia, so I didn’t pursue the MRI.

I tried to avoid touching the lump so that it would go away, but it didn’t. It grew slowly over a year until it felt like it was pushing on a nerve. I felt pain in the knuckles of my right index and middle fingers whenever I tensed my muscles with my arm extended, especially if my arm was above my head. I could no longer do push-ups or chin-ups without pain. I also thought that I had developed wrist and hand pain from typing too much as a software developer. I saw the doctor two years after the initial visit, and he ordered the MRI.

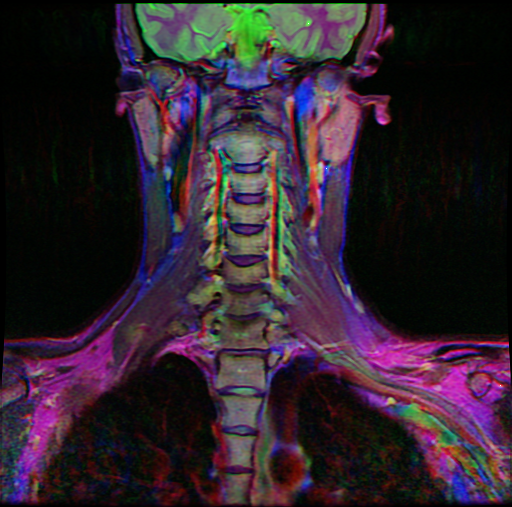

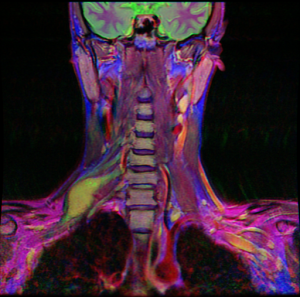

The MRI found a well-circumscribed nerve sheath tumor in the C7 spinal nerve. The C7 nerve is part of the brachial plexus, which innervates most of the arm. I felt foolish for having complete confidence in the first diagnosis and pushing the problem from my mind as soon as I heard good news. I should have returned to the doctor the moment the lump showed signs of growth, instead of continuing to believe it was just a muscle knot. I had looked at the CT scan afterwards, but only because I was curious to see my skull.

After the MRI, I was determined to not repeat my mistake. I scheduled an appointment with a neurosurgeon. Then I prepared for the visit by studying my MRI and learning as much as I could about the different nerve sheath tumors and their management. Doing my own research helped, because almost nothing that the neurosurgeon told me was a surprise. For example, I initially assumed that such a superficial lesion could be easily removed with only regional anesthesia, but online sources showed me that almost all brachial plexus tumors are removed with general anesthesia. I had never had surgery or been unconscious before, and it had always been extremely important to me to avoid being unrousable. I could not have handled the news about general anesthesia at a doctor’s office.

The neurosurgeon explained his whole plan for surgery. The tumor was probably inside the nerve, so he would have to identify an area without functional motor fibers where he could incise the mass and expose the tumor. To check a potential entrance point, he would apply electrical stimulation and look for a response. By avoiding cutting any part that could elicit a response, he would avoid harming functional nerve fibers. During stimulation, his team would look for movements in my arm. They would also measure the polarization of my arm muscles directly with electrodes inserted into each major arm muscle, a technique called electromyography. Electrodes in my scalp would show some sensory reactions. This neural monitoring precluded the use of nerve blocks or any other form of regional anesthesia. He had to use general anesthesia. When he located a good spot, he would cut the mass in the line of the nerve and then peel the nerve away from the tumor. If the tumor was a benign schwannoma, it would probably separate easily from the nerve. If it happened to be a neurofibroma, he might have to cut some nerve fibers running through the tumor. If the tumor appeared malignant or was invading the nerve, he would biopsy it and we would decide what to do later. The neurosurgeon was confident that he would not damage the motor part of the nerve during that surgery. He also showed me the smooth edges of the tumor in the MRI that suggested that it was non-aggressive and would be easy to remove. Vascular and orthopedic surgeons would be available in case he nicked one of the nearby major blood vessels or had to cut through the clavicle in order to reach the entry point in the mass.

The neurosurgeon examined my reflexes and the strength of my arm muscles. I mentioned that I had had a stripe of numbness along a rib on my right side for at least the last seven years. When he also observed hyperactive reflexes in my legs, he suggested an MRI of my thoracic spine.

I thought about the surgery for a while and then decided to schedule it. My only concern was that I would be under general anesthesia for two to three hours, which I thought was a long time.

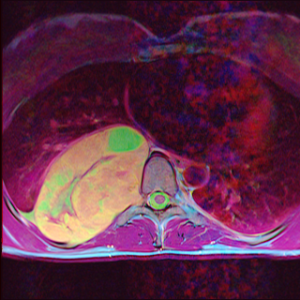

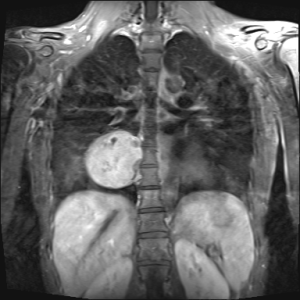

I got the thoracic spine MRI, and sure enough, another tumor explained the loss of sensation on my side. This tumor measured 10 x 7 x 6 cm. It was displacing part of my right lung, just above my diaphragm. A small bump approached the T8 neural foramen, where the spinal nerve exits the spine. It had the characteristics of another schwannoma. The neurosurgeon wanted to proceed with the neck surgery in order to use the first tumor as a sort of biopsy for planning the second surgery. In the second surgery, a thoracic surgeon would handle the approach while the neurosurgeon removed the tumor. They would remove the nerve with the tumor, because it was a minor nerve that was already damaged. It was almost funny that the lump in my right supraclavicular fossa had signaled a tumor in my chest, but in a way much different from what I’d feared two years earlier.

Discovering the chest tumor made me wonder how it was affecting me. I was surprisingly asymptomatic. I’d felt occasional strange sensations on the right side of my ribcage and abdomen since middle school. There were random shooting pains, muscle spasms, and muscle soreness. I hadn’t thought about it much because I’d felt like I’d always been that way. I’d subconsciously assumed that a symptom that didn’t change over years and didn’t bother me wasn’t a problem. Another thing I’d noticed was a lack of energy ever since college. Additionally, I’d noticed that whenever I told myself that I would take deep, relaxing breaths, I would return to shallow breathing within a few minutes. I’d assumed that the shallow breathing was due to stress. I still don’t know if the tiredness and unhealthy breathing were caused by the tumor, but I’m hopeful.

The location of the second tumor outside the spine didn’t explain my hyperactive reflexes, and with two tumors, more were likely. Luckily, the neck MRI included the base of my brain and didn’t show any cranial nerve tumors. The neurosurgeon ordered an MRI of my lumbar spine, and also an MRI of my brain, to be safe. The two MRIs were normal.

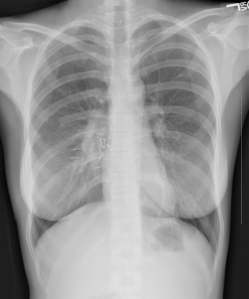

I wondered how fast the chest tumor was growing and whether it was at all visible in the CT scan from two year earlier. The CT showed the tops of my lungs, but no mass. Then I looked at the scout view, which looks like a plain x-ray and is used for adjusting the CT scan for the location and attenuation of the body part to be imaged. There was the tumor! My heart was on one side, and the tumor was on the other, making the image eerily symmetric. Obviously, no doctor had looked at the image for even a split second. I remembered looking at the image when I first received it and possibly thinking, “That looks a little odd,” but never giving it a second thought. I had believed that I was looking at all normal physiology because it had been reviewed by doctors.

I regretted not looking at the scout view a little more carefully, not asking questions about the muscle knot diagnosis and what future symptoms to watch for, and not getting the MRI that was offered. I knew that if one of the surgeries was seriously complicated by the size of the tumor that I wouldn’t be able to forgive myself for not taking a bigger role in my health care. There were so many ways that I could have been diagnosed sooner. I was determined to not make the same mistake again. This may not have been the best lesson to learn, because it could also lead to excess worry or hypochondria.

I immediately got a book on MRI and started reading my four MRIs. I also prepared for all subsequent doctors’ visits by reading relevant Wikipedia articles and free medical journal articles online. I prepared questions ahead of time and brought them to the office on a clipboard. Knowing some anatomy and being fascinated by biology made the task much easier. My involvement paid off once when I caught a minor mistake in a CT scan order.

Increasing my understanding was also my way of coping with feelings of utter helplessness. It was hard for me to accept the fact that I would be unconscious during an event that would have such life-changing consequences.

The hospital I went to doesn’t choose the anesthesiologist until the morning of surgery, so I couldn’t get an exact list of the drugs I would receive until I arrived. I learned that they would use propofol and fentanyl for induction. Luckily, I was allowed to opt out of premedication. They would use a muscle relaxant while inserting the endotracheal tube. Then they would use propofol, desflurane, and remifentanil for maintenance of anesthesia. If the muscle relaxant hadn’t worn off by the time they started the electromyography, they would reverse its effects with another drug. I learned afterwards that they had used a Foley catheter, presumably so that they would be prepared in case the tumor was very difficult to remove.

The first surgery went perfectly. It only took an hour and a half. The tumor looked like a schwannoma, and it came right out without the surgeon having to cut any nerve fibers. When I first awoke, my arm felt a little like blood flow was returning after I had slept on it. It felt completely normal after that. I was able to write in my journal while I sat in the hospital bed. I never experienced any pain, nausea, amnesia, or wooziness. Because of the anesthesia, I had to stay overnight with an IV fluid drip and a sequential calf compression device. I also received heparin shots. When I returned home, I could stretch out my arm without experiencing any of the pain that I had felt earlier. My neck was swollen and uncomfortable, but there was still no pain. I continued taking acetaminophen for several days to be safe.

Three days after the surgery, the sensation in my knuckles and the radial side of my forearm started to change. I experienced every sensation in that area as pain. If something touched me unexpectedly, I would think I’d been stung by a bug. Once I saw that something harmless was touching me, I could ignore the pain, so it wasn’t really a problem. This hypersesitivity slowly faded over a month or two. My arm feels completely normal now. Even most of the pain that I originally thought was caused by typing disappeared.

I had a week of relaxation and bliss after the surgery. Then I met with the thoracic surgeon to plan the second surgery. He explained that he would use an open approach for such a large tumor, especially with its proximity to the thoracic duct, larger pulmonary blood vessels, and right ventricle. He would probably use a posterolateral thoracotomy. That could be expanded with a transverse incision through the sternum, depending on what he found when he got in there. He also explained the recovery time and the large amount of pain inherent in chest surgery. It was a stressful appointment.

After a chest CT with contrast for surgical planning, a pulmonary function test, an additional office visit with each of the surgeons, and seven weeks of recovery, it was time. I also got a second opinion because it was a major surgery. Before the first surgery, I was terrified about what could go wrong, yet confident in my choice of treatment. My confidence was gone this time. The complexity was overwhelming.

The second surgery also had no complications. The anesthesiologist inserted epidural and IV catheters. Once I was in the operating room, he used propofol for “calming”, which wiped all memories from that point on. I didn’t get a complete list of the drugs used. He at least used propofol for induction. Then he used rocuronium or cisatracurium as muscle relaxants and propofol and sevoflurane for maintenance. He also gave drugs to manage blood pressure and reduce secretions. The team inserted an arterial line in my wrist, a second IV in my other arm, a Foley catheter, and a double-lumen endotracheal tube. Then the thoracic surgeon did a posterolateral thoracotomy at the right T6-T7 intercostal space. He spared the serratus anterior muscle but cut part of the latissimus dorsi. Then he removed a segment from the back of the seventh rib. This allowed the rib to bend farther out of the way during surgery while preventing the cut ends from scraping after he closed the incision. He then retracted the ribs and exposed the tumor. Since the tumor had the characteristics of a benign schwannoma, he decided that it was safe to remove it in pieces. Fortunately, the tumor did not adhere to the surrounding lung or vascular structures. It was only firmly attached to the chest wall. The surgeon removed the bulk of the tumor along with the overlying parietal pleura, leaving only the protrusion into the spine. Then he clipped the medial cut edge of the pleura to avert a chyle leak. At this point, the neurosurgeon took over and removed the last piece of tumor, along with the attached spinal nerve. He ligated the base of the nerve to prevent a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Finally, the thoracic surgeon inserted a chest tube for draining fluid, and closed the incision. While closing the ribs, he sutured the lateral cut end of the seventh rib against the sixth rib, for stability. The surgery took a total of two hours.

I woke up in the operating room and was rushed to the post-anesthesia care unit. A large area on my right side was numb, but I felt no pain. I assumed it was the epidural anesthesia. The arterial line, urinary catheter, and endotracheal tube had already been removed. My abdominal muscles spasmed uncomfortably. The nurse thought that the abdominal discomfort was my bladder, so she kept me there longer. I was eventually moved to a room. I walked to the new bed while a nurse helped me manage the tubes. Then I started experiencing premature ventricular contractions, which scared me. A blood test showed that I had low blood magnesium. That was easy for them to correct, and my heart beat returned to normal.

I didn’t get any sleep the first night because nurses took my vitals every hour, and I struggled to find a comfortable position among all the tubes. When I rolled onto my right side, my heart rate became irregular until I rolled back. Later, my bladder filled, but the epidural prevented me from urinating. I had to compress my bladder with my fist. Even though there was no pain, I felt lots of strange, uncomfortable sensations. My right lat felt fragile, like it would break if I tensed it. I also felt something scraping the back wall of my chest with each breath. I later learned that it was the chest tube, because it stopped the moment the tube was removed. The patch of numbness didn’t cover the chest tube hole, either. At 6:00am, someone arrived with a stretcher bed to transport me down for my daily chest x-ray. I almost lost it. I had used up all of my patience, and I was extremely tired. I also wasn’t used to the inactivity or restraint required when you are hooked up to a chest tube, other tubes, and a sequential compression device. I had gone for a run every day for the past ten days, and I had a hard time containing myself. Luckily, I completed the x-ray without doing anything I regretted. I slept a little and gradually became accustomed to lying in the hospital bed.

The next day, I became nauseous and developed a headache. None of the drugs that the nurses gave me helped. I still struggled to urinate. Emptying my bladder enough to avoid a catheter took all of my willpower. I felt awful. I did breathing exercises with an incentive spirometer and walked down the long hallway multiple times per day. The chest tube was annoying because it needed continuous negative pressure to keep my lung from collapsing while it drained excess fluid. When I was in my room, it was hooked to a suction tube built into the wall. Whenever I got up, a nurse had to switch the suction to a noisy battery-powered machine while I held my breath. Then I had to push the machine around in an office chair while someone else pushed the IV stand. A nurse had given me a scopolamine patch for nausea, and it changed my vision in a way that made me feel disoriented while walking. I also couldn’t wear contacts because my eyes were too dry.

The nausea and headache were the worst, but I eventually realized that lying flat relieved them. I could keep food down if I sat up, wolfed the food, and then lay down immediately. A doctor removed the epidural on the third day. I didn’t feel much difference, because the numbness was actually caused by nerve damage. The surgery had doubled the width of the original numb stripe and also increased the numbness so that the skin and underlying ribs felt dead. There must have been a little sensation before. The main reason that I was still at the hospital was the chest tube. I couldn’t go home until the drainage decreased below a certain rate, the tube was removed, and a doctor determined that my lung was not collapsing without the drain. The doctor finally removed the chest tube on the fourth day. What a relief! I still felt nausea and a headache when I sat or stood, though. A little air had entered my chest when the doctor pulled out the chest tube, so I needed another follow-up x-ray to show that the air bubble wasn’t growing. By the time I was allowed to go, it was late, so I left early on the fifth morning after surgery.

I was given many drugs during my hospital stay. I received intermittent boluses of bupivacaine and hydromorphone through the epidural, which I could supplement with the press of a button. I also received fluid through my IV for the first day or two. I took acetaminophen and naproxen for pain. I was given IV ondansetron and metoclopramide for nausea, and a scopolamine patch when those weren’t enough. After the epidural was removed, I took several doses of oxycodone.

After a nauseating ride home, I weighed myself and found that I had lost ten pounds during my hospital stay (the tumor was only a half pound). My new weight was 110 pounds, and I looked skinnier. I continued to feel sick whenever I stood. After some initial lightheadedness, the bad sensations would increase until I lay down again. I would feel dizzy, disoriented, and nauseous and get a headache. I also experienced ear effects; normal sounds seemed to pulse in intensity with each step I took, and I felt like my head was underwater. I only stood up for a few minutes at a time. When I tried taking a shower, I felt sick for the next six hours. Even lying down didn’t relieve my symptoms entirely, because I still had trouble concentrating. I felt so lucky that I wasn’t also experiencing pain. I don’t know how I would have also handled the side effects of the narcotics. I had gone off the other drugs, too. When the symptoms didn’t show any sign of improvement for almost a week, I started to worry that something had gone horribly wrong during the surgery, and that I wouldn’t ever be able to adapt to standing again. None of the nurses I talked to could offer much encouragement, with advice like, “Call back if you’re still having trouble in a few days.” I used a phone to search the internet from the couch and couldn’t find any help there, either. My symptoms most closely matched orthostatic intolerance, and it seemed to only have scary causes. One nurse suggested sucking in my abdominal muscles. I couldn’t believe how well that worked. It allowed me to stand longer, though I still wasn’t normal.

Two days later, during my first follow-up appointment, I was told that my symptoms weren’t completely unusual after major surgery. My fluid balance could take up to six weeks to normalize, due to the residual anesthesia drugs in my body. My hopelessness vanished. I could handle six weeks of inactivity, but not a lifetime.

The only other negative surprise was when the pain started on the seventeenth day. I’d wondered when feeling would return to the new numb area, but I hadn’t expected it so soon. I first felt pins and needles on my skin. Then my seventh rib, which had been cut, started to ache along its entire length. I had noticed that it was sticking out farther than the adjacent ribs, so I tried to push it back. That didn’t work. I resumed taking acetaminophen, with oxycodone at night. It hurt to lie down, so I had to alternate between sitting and lying in order to balance the pain and nausea. Four days later, the pain abruptly stopped. My skin once again felt completely dead. I didn’t really know what was going on, but I couldn’t help imagining my seventh intercostal nerve trying to repair itself while the pericostal sutures or corners of the cut rib threatened to crush it again. Their movements were completely invisible yet were the difference between comfort and pain. I was expecting pain from the start, so this didn’t bother me too much.

My recovery has been going well so far. I’ve seen steady improvement in my ability to remain upright. Breathing feels so much easier now; the loss of lung capacity had been too slow to notice before the surgery. I also no longer feel the weird pain in my side. It’s possible that the cut nerve or the area that is temporarily numb will eventually cause other unpleasant sensations, but I won’t know for a while. I also won’t know how well I’ve recovered until I’m allowed to exercise.

If I continue to recover as I have, I will be happy with the results. I’m glad that the two year delay didn’t worsen the outcome. If anything, I’m lucky that the tumors presented exactly as they did, because it enabled accurate preoperative diagnosis. My only regret is that two schwannomas means more. I’m getting genetic testing to see if this is only segmental schwannomatosis. Since it doesn’t run in my family, and the tumors were relatively close, there is a chance that only part of my body has the mutation. I have yet to find out what scans I’ll need for future monitoring.

I can’t believe how many amazing, caring people in the healthcare industry I met during this ordeal. The surgeons did an incredible job of making my problems just vanish. I’m really grateful. I’m also grateful for my family and their support.

Update – August 1, 2015

My ability to stand gradually improved, until I could remain upright all day by two months post surgery. However, a constant, low-grade headache started when I woke up on the 34th day after surgery. Since any movement worsened the pain, I avoided traveling anywhere. I occasionally felt nauseous, especially in the morning. Luckily, I was able to work from home.

Nothing I tried seemed to help the headache, including seeing a chiropractor and a physical therapist. I finally saw a neurologist after four and a half months. His theory was that I’d somehow developed a cerebrospinal fluid leak during the surgery, which caused the first headache. My neck muscles tightened in response to the pain. Then the CSF leak resolved, but my neck muscles continued to tighten, causing a second headache. The muscle tightness in response to pain created a vicious cycle, and he recommended neck exercises to break it.

After trying the neck exercises, I saw a massage therapist who was highly recommended. I saw her once a month, and my headache disappeared for a few hours each time, as if by magic. I also started having days where I didn’t feel my headache at all, unless I shook my head. The overall pain was decreasing, too, but so slowly that I didn’t know it at the time.

Finally, nine and a half months after the surgery, I noticed that my headache was gone. It went away so gradually that it hardly bothered me for the last couple of months. Now, even shaking my head doesn’t trigger the pain. I can finally run again. I admit that I was slightly disappointed that I didn’t see a dramatic improvement in speed without the tumor compressing my lung.

The nausea also gradually improved, though I still feel a lack of appetite and a decreased interest in food and cooking. I’ve only regained five pounds since the surgery.

I still haven’t regained sensation in my side or experienced any nerve pain.

I had follow-up MRIs of my right brachial plexus and thoracic spine at four months, both with contrast. Neither one showed any remaining tumor. I have to repeat the two MRIs at one year and three years. The neurosurgeon didn’t recommend any more screening MRIs.

I also followed up with genetic testing of the chest tumor and the rest of my body. I learned that I have a constitutional mutation in the schwannomatosis gene SMARCB1. The tumor contained cells with an additional mutation in the neurofibromatosis type II gene (NF2), as well as only one copy of chromosome 22. Since SMARCB1 and NF2 are both on chromosome 22, that means that those cells had lost all four copies of the two genes. Complete inactivation of those genes explains the tumor development.

I’m still very happy with how things turned out, except for the possibility of more tumors.